Discussing the virtues or follies of the natural wine phenomenon and its cult like following has been a favorite pastime for wine professionals for a couple of years now. Lately it has also spread to consumer magazines and wine aficionados pounce on the opportunity to finally take a stance (which is mostly expressed in poorly worded pastiches on Facebook along with much virtual back-slapping). There is little, if any, real discussion. Frankly, I am bored to tears with the whole thing, and in a way torn as to whether or not I should delete this whole tirade and ignore the topic, instead of adding fuel to anyone’s fire. But on the other hand, if I can just publish my views I can just refer to that and move on to more interesting discussions next time I meet someone in the wine trade, who without a doubt will bring the topic up within the first ten minutes of conversation.

During the last MAD symposium, where luminaries in the world of gastronomy descend on the town for cutting-edge seminars and happenings, I heard the following repeated almost ad nauseum by big-shot international chefs, winemakers and sommeliers who just had to visit all the “cool” restaurants while they were here:

“What the hell is going on in Copenhagen? The food is spectacular; delicious and intellectually challenging, but why is everyone serving undrinkable wine? Of course, I have to remain diplomatic and would never say it out loud.” Some of the more wine-savvy visitors lamented, “They’re not even serving any good natural wine! The more obscure and faulty the better!”

Copenhagen, where I live and work, has in the last few years become a Medina (not quite up to Mecca standards) of natural wine. This is, of course an effect of Noma becoming the most talked about restaurant in the world a few years ago. Noma’s dogmatic approach to rediscovering and interpreting local ingredients resulted in a light, vegetable-driven cuisine with overtones naturalistic purity. Creativity through constriction, you could say. The same radical dogmatic applied to the wine list results in a selection of exclusively European wine, made by using methods of biodynamic agriculture (or at the very least organically, if the farmers beard was deemed long and raggedy enough) without additives, including sulfur dioxide.

Sulfur has been used as an anti-microbial and anti-oxidative agent in winemaking since Roman times. It can be added at various stages in grape growing and winemaking. Without it, wine is prone to spoiling, losing their aromatic freshness and turning brown. However, sulfur is an irritant and there are limits set on its usage. Most winemakers agree that it should be kept at a minimum (optimally only used at bottling), and a few brave souls work without it, or with extremely small quantities. Especially wine made for export usually needs to be protected, unless it can be shipped carefully in refrigerated containers and trucks, which adds a significant cost, and frankly doesn’t happen very often.

Now, back to Copenhagen, via Paris. Although the natural wine scene had been slowly stirring ever since Jules Chauvet convinced a handful of Beaujolais winemakers change their ways in the early 1980’s, it was only 20 years later that the movement gained enough critical mass to really make itself known. Paris especially became a hotbed of wine bars and restaurants featuring only vin nature. These places were edgy, cool and contrarian. They had a clear message and a very black-and-white view of the world: either you were with them or against them. Perfect for anxious foodsters.

Paris is a given on the top list of destinations for any restaurant professional searching for inspiration. Ambitious young chefs and sommeliers everywhere sucked it all up, and by 2007 there were major vin nature outposts in London, New York and Copenhagen. Aforementioned Noma and Bocuse d’Or winner Rasmus Kofoed’s Geranium, also a natural wine outpost, were the hottest places in Copenhagen, booked for months in advance and attracting fledgling and determined volunteer staff from all over the world.

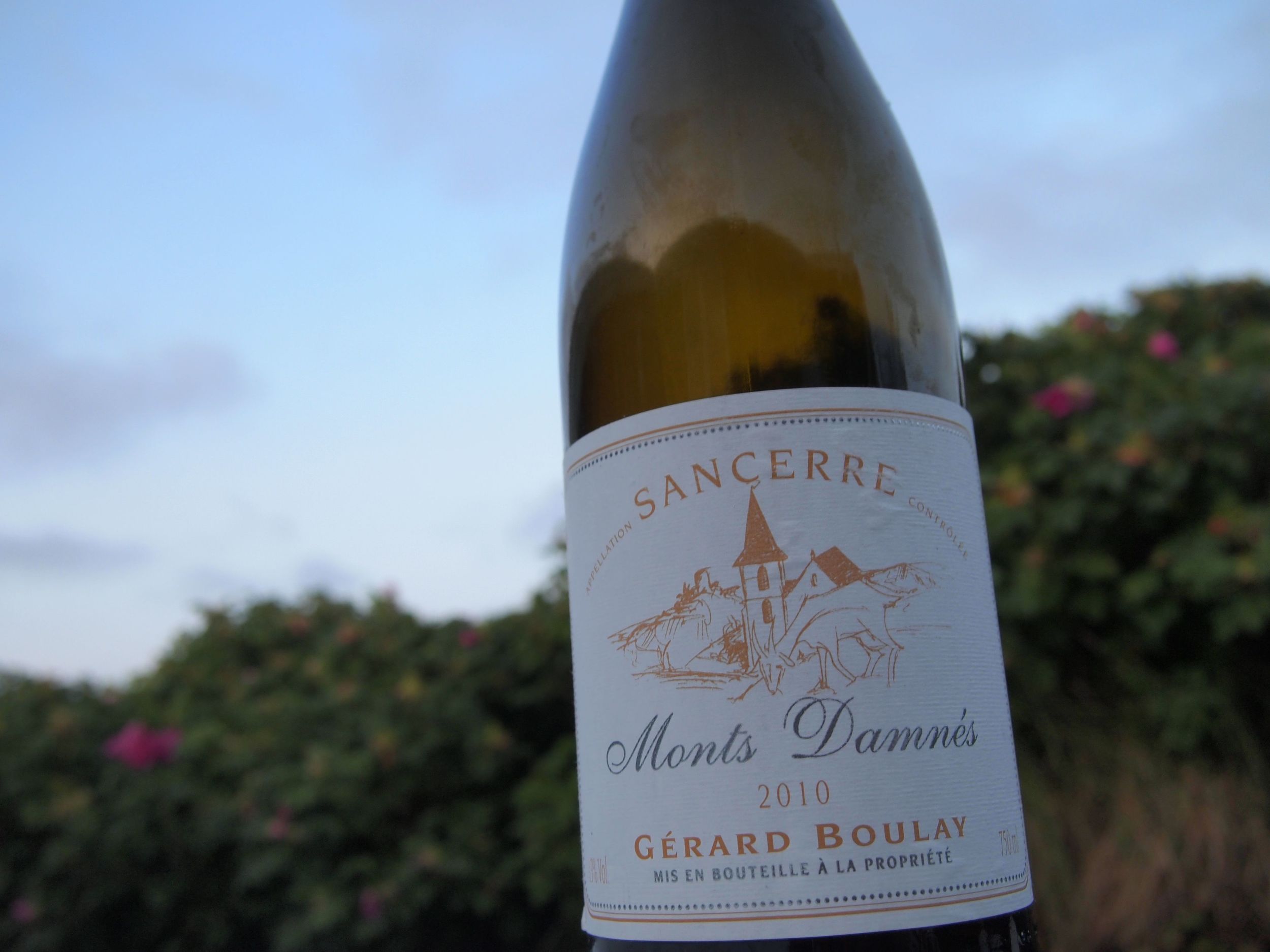

Let’s get personal. Back in 2008, when I started my career as a sommelier for real, I was quite drawn to the idea of vin nature. I was (and am still) attracted by the philosophy itself. But it was also a way to be radical and rebellious, to take a stance, seem cool and score all the hippy wine chicks (no, not really, they don’t exist). I read a lot, tasted a fair bit, bought a little and sold almost nothing. Perhaps I was in the wrong, way-too-uncool place. Either way, the interest was not quite there. What did best was those wines which even in classic renditions play around with oxidation; especially Champagne, Loire valley whites and wines from the Jura Mountains in France. The wines made by small, environment-conscious producers here, with minimal intervention clearly had a sense of life and intensity about them that their more conventional peers often (definitely not always) lacked. On the other hand, I never got into the more aromatic white grapes vinified without sulfur (like Riesling). I also generally struggled with the taste of many reds, which often end up with drying, rancid hazelnut-like tannins on the finish. This seems to be a clear sign of oxidation and a sensation that can ruin a wine for me, even though the flavor otherwise might be clean.

Two styles of wine more than any other drew me back from the absolute abyss though. German Riesling with residual sugar and Sherry. These wines literally cannot be made with completely natural principles, both requiring additions of different sorts. Despite this, they are undisputedly unique and belong to the pantheon of the world’s greatest wines. So if I had to forgo the beauty of a Mosel Kabinett with its unparalleled capacity for transmitting terroir, to fully embrace the vin nature dogma, something was seriously wrong. Even though my wine lists today are made up of 99% conventional wine, I still keep some vin nature favorites on there, (admittedly mostly for myself and other sommeliers). Usually I go for “the classics”, wines that won’t offend and stay true to the typicity of their appellation, but still offer personality and a good story. When I dine out I have natural wine on a regular basis, but I am very picky with what I choose and I have learned to stay far away from wine pairing menus, where I commonly find too many blatantly faulty and unpleasant wines.

Back to the restaurant scene in Copenhagen. Those hard-working poor souls who managed to live through years of brutal 80-hour weeks have now graduated, and Noma-alumni restaurants are popping up like mushrooms. With them follows the wine philosophy they’ve been steeped in, accentuated by the radicalism of youth (and freedom?); sulfur is not just unnecessary but plain evil. White wine is supposed to be brown, or at least orange. Red wines are supposed to foam a little. Champagne is for philistines; you should have (and enjoy) some Grolleau based pet-nat from the Loire. The more muddy sediment that ends up in the iso-glass (chosen with calculated nonchalance) the better.

And here is the crux. The sommeliers that run these lists often lack proper wine education, and points of reference to conventional wine (for lack of a better term). If a classic Meursault somehow crept under their radar, they woulnd’t know how to relate to it. They have worked for their entire professional career with only vins natures and have effectively missed out on 99% of the world of wine. They have been infused with the dogma that everything else is not only different, but it is stuffy, without interest or just plain evil. Their view of what wine is supposed to be is skewed so far away from mainstream that they lose all connection with reality and the palates of their guests. But bolstered by trend-sensitive media and anxious foodsters they feel invincible. It is a perfect parallel to that classic Danish tale of the emperor and his new clothes.

These “sommeliers” may never have tried a classic Bordeaux, and in fact many of them scoff at the notion. I have heard statements like “Cabernet Sauvignon is a shit grape”, “Real wine can not be made outside of Europe”. They fake sneezing attacks when you approach them with a glass of wine with added sulfur (yet somehow manage to drink Perrier or San Pellegrino water on the side without any issues, both of which are high in sulfur). For them, there is no need to try a wine from South Africa. It is inherently bad.

Now, I may be too harsh, but I have simply been served too much decidedly faulty wine in otherwise respectable establishments to let this slide, and then been chided when I pointed this out. No, maderization or rampant volatile acidity is not a sign of terroir, and it never will be. In fact, if all your white wines taste like lambic, no matter where they are from, why not serve beer instead?

That faulty wine is being served to such a degree is creating an unfortunate polarization. Where a few years ago the naturalists (sic!) were the aggressors, today they take a more actively defensive stance. Late-to-the-party winelovers exclaim their hatred of natural wine, scoff and laugh at biodynamic practices, wear “I heart SO2”-teeshirts and in general dedicate way too much time on social media talking about something they could as easily ignore.

Because, really, there are magnificent natural wines and it would be an equal shame if passionate wine drinkers take the contra-contrarian stand and dismiss the whole genre based on a few bad experiences. The wines of Pierre Overnoy in the Jura, of Dard & Ribo in Rhône, Catherine & Pierre Breton in the Loire along with many others deserve to be on as many great wine lists as possible.

All of this conflict because we don’t understand the virtue of moderation. No matter what you think of the most hardcore natural wine, you can not deny that the phenomenon itself has been great for the world of wine as a whole. When I meet winemakers in South Africa, Portugal or even the epicenter of evil wine capitalism; Napa Valley, they all express the desire to use as little intervention as possible and make pure, lively wine. Organic and biodynamic practices are becoming de rigeur everywhere, and for the right reasons too. You would have to be totally daft to think that that is bad in any way. In a way, the natural wine movement has also helped propelled the new interest in traditional wine. All of a sudden the wines of Bartolo Mascarello, López de Heredia, Gentaz and Clos Rougeard are back in style. It is long overdue.

I prophesize that the term natural wine will fade away over the next ten years, to be replaced by something infinitely better and more powerful. The trend has certainly peaked, and the fact that we cannot yet agree upon what natural wine really is shows how fickle it is. It is also time for the naturalistas to grown up and drop their elitist and borderline racist (again, remember good wine can not be made outside of Europe) views. I hope and think that we can shift focus to something much more important: wine with soul and personality. Let’s leave the devil in the details. If we need a label we could call it authentic, artisanal or just real wine (by the way, when was the last time you had some unicorn wine). It would include the best of the natural group along with classic producers like Vega Sicilia, but also leave room for Eben Sadie and his friends in South Africa, Araujo in Napa and Pontet-Canet in Bordeaux. Hell, we can even find a way to bend the rules to allow Penfold’s Grange in there somehow I am sure, despite its apparent lack of terroir. Let’s be inclusive for once and accept the fact that multitudes make the world a fun (and tasty) place to be.

Let’s end this rambling mess with some quick tips.

TIPS FOR VIN NATURE “SOMMELIERS”

- Stop being elitist.

- Help yourself to a proper wine education. Read the books and drink the wines. If you decide to limit your knowledge to 0.1% of the world of wine, you don’t have the right to call yourself a sommelier. I’ll even help (with the drinking part)!

- Don’t buy wine on good stories or length of winemakers’ beards.

- Don’t try to pass on faults as terroir. You should at least be questioning yourself and your palate if someone sends a bottle back.

- If you’re going to sell un-sulfured wine, invest a properly cooled cellar. I bet this is actually the cause of a majority of the faulty wines you’re serving.

TIPS FOR CLASSICALLY MINDED WINOS

- Drop the polemic bullshit.

- Give natural wines a chance. Go for the producers that have been doing this since before there was a term and a trend for it. As with anything else, they are usually the most consistent.

- Be thankful for all that the movement of organics, biodynamics and natural winemaking has done for the world of wine. It's brought another level of consciousness to conventional producers as well.

TIPS FOR JOURNALISTS AND BLOGGERS

- Enough with the sensationalism. If things seem black/white it’s only because you don’t know better.

- Dare to criticize, even if your peers are praising.

- Realize that in today’s world, you’re powerful. Take responsibility and act accordingly.

TIPS FOR NATURAL WINEMAKERS

- Realize that you’re in a bubble before it’s too late and get your shit together.

- Your French witticisms really aren’t all that funny. The naked girl on the label doesn’t exactly help neither.